Features - Business

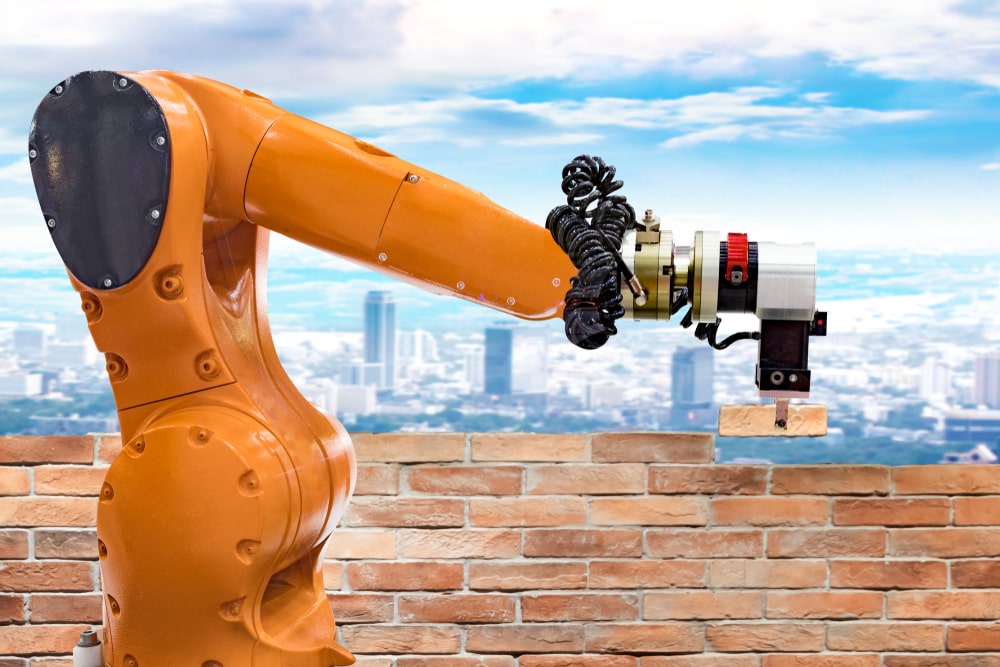

The robotization of the construction industry

The British construction industry could be described as a sector which is infamously averse to change. In fact, when taking into account the digital revolution which has swept the world, it was the Institute of Civil Engineers who pointed out that the construction sector was the second least digitised in the country, with only agriculture lagging behind.

It would not be completely unfounded to suggest that the construction sector is slow to adopt advancements in technology.

Therefore, considering robotics comprises one of the subcategories of technology, why would construction be any quicker to undergo robotization?

How robotised is the current construction industry in the UK?

According to a report published by the ING Group, European building companies are one of the top contenders in regard to the utilisation of robotics, competing with the likes of Japan, China, and the United States. However, upon closer inspection, it’s easy to see that the UK has had very little to contribute to the continent’s position in the world rankings. When looking at the contributions made by individual European nations, it becomes clear that the Netherlands and Belgium have carried the figures for Europe as whole, with each of the countries possessing an average of 1.5 robots per 10,000 workers. While Germany and the UK possess surprisingly meagre figures by comparison, with 0.8 and 0.3 robots per 10,000 workers respectively.

Adding to this is the fact that the use of drones has increased exponentially, with drones undeniably falling under the label of robotics. Furthermore, it has been forecast by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) that there will be 76,233 drones in operation in the UK across all sectors by 2030, with 4,816 of these being employed by the construction and manufacturing sectors. Currently, drones are operated by construction companies such as Skanska, for purposes such as mapping, and are likewise used to observe degradation of infrastructure such as motorways and railways.

However, has robotics in the UK construction industry taken a step beyond purposes such as observation? And are they on the verge of replacing labourers, masons, and craftsmen?

What is an example of robotization in the UK construction industry?

Perhaps one of the most advanced examples of robotics in UK construction is SAM, the semi-automated mason. SAM is, as the name suggests, a semi-automated bricklaying robot that is designed to work in partnership with a mason, resting upon a set of tracks which can be installed within half of an hour and can be programmed to lay bricks in formations detailed by map files uploaded via USB. The level of technology implemented by SAM then goes a step further, with the semi-automated mason also using a laser sensory system which allows the robotic labourer to adjust to any changes on the working platform. This means that SAM can self-adjust so that each individual brick is accurately and perfectly placed, every single time.

Although it may seem that SAM’s arrival has made the role of the bricklayer practically redundant, construction workers can rejoice in the fact that SAM is only semi-automated, and thus requires an operator to work alongside. So, for now, labourers remain irreplaceable. But, with the rise of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, is the likelihood of human obsoletion one of the main reasons behind the UK construction industry’s slow adoption if robotics?

Why has the UK construction industry been slow to adopt robotization?

One of the most pressing reasons for the delay in adopting robotics into the British construction sector is the fear of a subsequent wave of unemployment. It follows, in the minds of many people, that a continual advancement in technology will eventually result in labourers being replaced by machines.

The Chair of the Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee, Rachel Reeves MP, highlighted this point perfectly when she stated: “The switch to automation brings challenges for businesses and for workers, with fears for livelihoods or disruption to job roles coming to the fore.”

But the Labour MP continued to explain other hindrances to the robotization of the construction sector by highlighting that politicians and businesses have not imposed a strategic approach, to ensure the industry’s smooth transition from being manual labour orientated to being automated.

She added: “The Government has failed to provide the leadership needed to help drive investment in automation and robot technologies. If we are to reap the potential benefits in the future of improved living standards, more fulfilling work, and the four-day working week, the Government needs to do more to support British businesses and universities to collaborate and innovate.

“The Government should come forward with a UK Robot and AI Strategy to support businesses and workers as they manage the transition to a more automated world of work. This new Strategy must seek to get the right support in place, on issues such as skills, investment and training, to ensure that all parts of the UK share in the jobs and growth benefits offered by automation.”

How is a lack of robotization detrimental to the UK construction industry?

In an extremely competitive international market, keeping up-to-date with the latest advancements which can boost productivity, namely advancements in technology, are imperative for maintaining pace with competitors. Therefore, should the British sector fall behind on the international market, it would be to the detriment of the British economy and subsequently also the British job market.

MP Reeves concluded: “The real danger for the UK economy and for future jobs growth is, however, not that we have too many robots in the workplace but that we have too few. For all the potential of the UK, and despite our excellent tech and research base, the fact is that we are lagging behind our international competitors in our adoption of robot and automation technologies. Productivity, economic growth, and ultimately job-creation and higher earnings, will flow to those countries that capitalise on these technologies.”

If you would like to read more articles like this then please click here.

Related Articles

More Features

- Ten years of progress on payment, pre-qualification and skills

19 May 25

The industry has made significant progress on late payment, pre-qualification, and competence since the formation

- Pagabo provides clarity on impacts of new NPPS and PPNs

12 Mar 25

The Labour government’s new National Procurement Policy Statement (NPPS) sets out strategic priorities for public

- How is the Procurement Act going to drive social value

24 Feb 25

The regulations laid out within the Procurement Act 2023 will go live today.